Neurotransmitter Testing

Why Neurotransmitter Testing?

Neurotransmitters are your body’s chemical messengers. They carry messages from one nerve cell across a space to the next nerve, muscle or gland cell. These messages help you move your limbs, feel sensations, keep your heart beating, and take in and respond to all information your body receives from other internal parts of your body and your environment. We do neurotransmitter testing to check how well your neurotransmitters are functioning.

What are neurotransmitters?

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers that your body can’t function without. Their job is to carry chemical signals (“messages”) from one neuron (nerve cell) to the next target cell. The next target cell can be another nerve cell, a muscle cell or a gland.

Your body has a vast network of nerves (your nervous system) that send and receive electrical signals from nerve cells and their target cells all over your body. Your nervous system controls everything from your mind to your muscles, as well as organ functions. In other words, nerves are involved in everything you do, think and feel. Your nerve cells send and receive information from all body sources. This constant feedback is essential to your body’s optimal function.

What body functions do nerves and neurotransmitters help control?

Your nervous system controls such functions as your:

- Heartbeat and blood pressure.

- Breathing.

- Muscle movements.

- Thoughts, memory, learning and feelings.

- Sleep, healing and aging.

- Stress response.

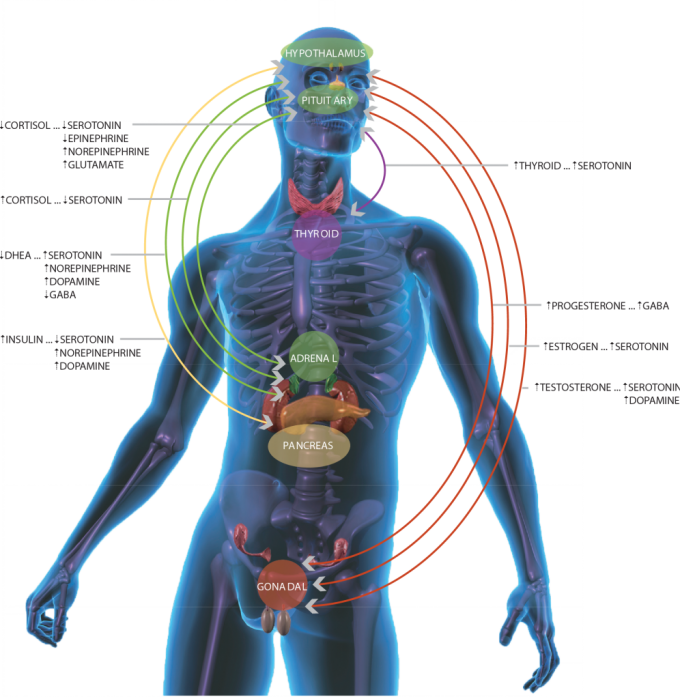

- Hormone regulation.

- Digestion, sense of hunger and thirst.

- Senses (response to what you see, hear, feel, touch and taste).

How do neurotransmitters work?

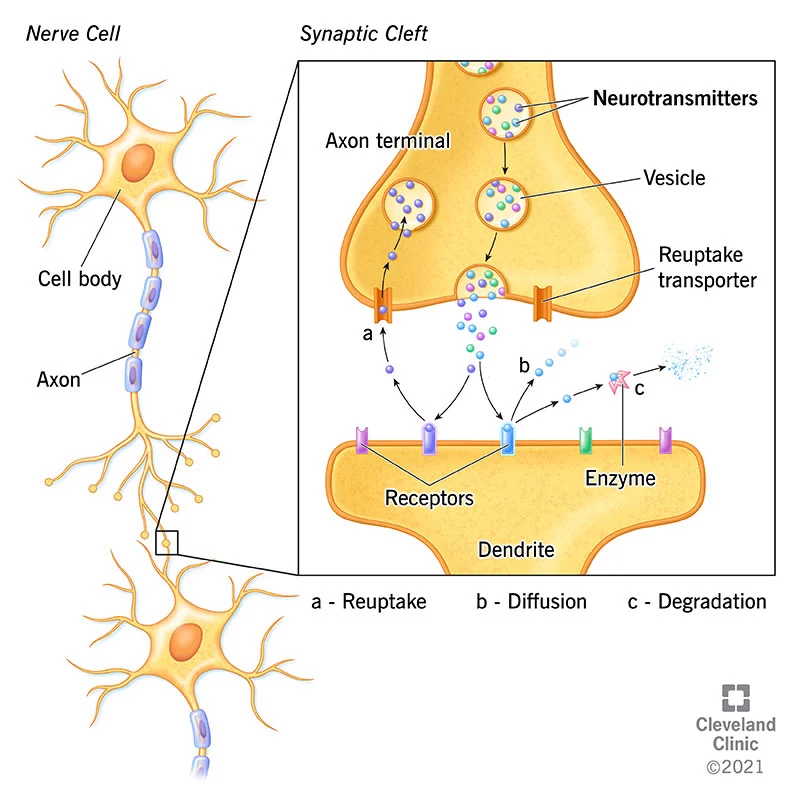

You have billions of nerve cells in your body. Nerve cells are generally made up of three parts:

- A cell body. The cell body is vital to producing neurotransmitters and maintaining the function of the nerve cell.

- An axon. The axon carries the electrical signals along the nerve cell to the axon terminal.

- An axon terminal. This is where the electrical message is changed to a chemical signal using neurotransmitters to communicate with the next group of nerve cells, muscle cells or organs.

Neurotransmitters are located in a part of the neuron called the axon terminal. They’re stored within thin-walled sacs called synaptic vesicles. Each vesicle can contain thousands of neurotransmitter molecules.

As a message or signal travels along a nerve cell, the electrical charge of the signal causes the vesicles of neurotransmitters to fuse with the nerve cell membrane at the very edge of the cell. The neurotransmitters, which now carry the message, are then released from the axon terminal into a fluid-filled space that’s between one nerve cell and the next target cell (another nerve cell, muscle cell or gland).

In this space, called the synaptic junction, the neurotransmitters carry the message across less than 40 nanometers (nm) wide (by comparison, the width of a human hair is about 75,000 nm). Each type of neurotransmitter lands on and binds to a specific receptor on the target cell (like a key that can only fit and work in its partner lock). After binding, the neurotransmitter then triggers a change or action in the target cell, like an electrical signal in another nerve cell, a muscle contraction or the release of hormones from a cell in a gland.

Why would a neurotransmitter not work as it should?

Several things can go haywire and lead to neurotransmitters not working as they should. In general, some of these problems include:

- Too much or not enough of one or more neurotransmitters are produced or released.

- The receptor on the receiver cell (the nerve, muscle or gland) isn’t working properly. The otherwise normal functioning neurotransmitter can’t effectively signal the next cell.

- The cell receptors aren’t taking up enough neurotransmitter due to inflammation and damage of the synaptic cleft (see myasthenia gravis).

- Neurotransmitters are reabsorbed too quickly.

- Enzymes limit the number of neurotransmitters from reaching their target cell.

Problems with other parts of nerves, existing diseases or medications you may be taking can affect neurotransmitters. Also, when neurotransmitters don’t function as they should, disease can happen. For example:

- Not enough acetylcholine can lead to the loss of memory that’s seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

- Too much serotonin is possibly associated with autism spectrum disorders.

- An increase in activity of glutamate or reduced activity of GABA can result in sudden, high-frequency firing of local neurons in your brain, which can cause seizures.

- Too much norepinephrine and dopamine activity and abnormal glutamate transmission contribute to mania.

This is why neurotransmitter testing is such plays such an important role in our overall health.